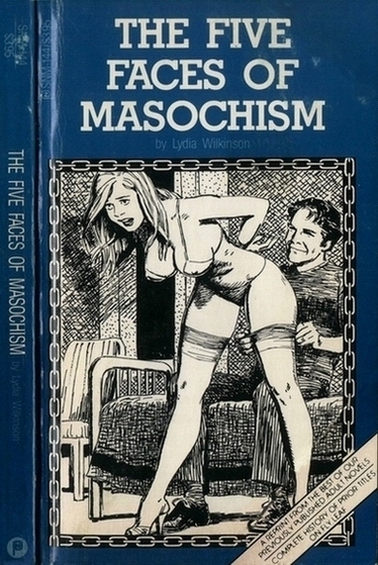

Lydia Wilkinson

The five faces of masochism

INTRODUCTION

A work bearing the title of The Five Bloods of Ireland would need no justification for its title other than that the contents of the work deal with the five principal septs or families of Ireland, i.e., the O'Neils, the O'Connors, the O'Briens, the O'Lachlans, and the M'Murroughs; a title of The Five Nations would likewise be as easily justified if the work dealt with the five confederated Indian tribes (the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas), or, as was the case with Rudyard Kipling's volume of poems, if "the five nations" were the five component parts of the British Empire.

Similarly, a title such as The Five Faces of Masochism would, understandably, suggest to the reader that there are but five – no more and no less – forms or manifestations of that certain peculiar facet of human behavior, or misbehavior, to which Richard von Krafft-Ebing in the latter part of the nineteenth century gave the name of masochism. Such a suggestion, it should be stressed at the very outset of this work, is not intended to be anything other than one of convenience – the "masochistic scale" of five simply meaning to reflect the degree or severity of masochistic tendencies and should not be allowed to dominate the reader's thought as anything other than a comparative aid. Suffice it to say that, in the opinion of this author, the majority of people – the psychological median, so to speak – would probably fall within "masochism one" and "sadism one" range. Somewhere between these two, at "zero", the masochistic and the sadistic inclinations are in a state of equilibrium, or, to put it in other words, are both weak and simultaneously equal, thereby canceling each other out. As one ascends, or descends, the abstract scale in either direction toward "severity five", the misbehavioral aspects of the individual's condition rapidly approach a psychopathological state. A condition of extreme masochism or of extreme sadism – "severity five", that is – is a relatively rare state of psychosis and is not included in this work. It would not be improper to say that those unfortunate souls who fall within those narrow ranges of psychopathology are seldom available to a private-practice psychiatrist, primarily because "masochist five" is quite often dead, whereas "sadist five" is either in the asylum or is incarcerated.

If one is ready to accept the implication that both masochism and sadism or either the one or the other is present in every individual in "different concentrations", so to speak, then it is an inevitable conclusion that the world is, in fact, made up of the two groups, and the question, then, seems to be not whether one is a masochist or a sadist, or has one or the other inclination, but rather, how much of a masochist or a sadist one is.

Is such a deduction absurd? Not if one studies the history of mankind, and not if one accepts the three definitions of masochism as they are presented by J. P. Chaplin, Professor of Psychology at the University of Vermont and author, in his Dictionary of Psychology. He states that masochism is:

1. a sexual disorder in which the individual derives satisfaction from the infliction of pain upon himself. Pain may be a prelude to, or an accompaniment of sexual relations, or its application may be sufficient in and of itself to induce orgasm.

2. more generally, the enjoyment of suffering or a tendency to seek opportunities for being offended or hurt.

3. (Psychoan.) the turning inward of the destructive tendencies or thanatos.

Chaplin's definition of sadism is, for some reason, less all-encompassing, limiting itself to the sexual side of sadism. He states:

[Sadism is] a sexual perversion in which sexual satisfaction is associated with the infliction of pain.

All one needs to do, however, to complete the picture of the masochism-countering tendency of sadism is to paraphrase Professor Chaplin's definition of masochism. Sadism, then, more generally, may be taken to be "the enjoyment of suffering [in others] or a tendency to seek opportunities for… offend[ing] or hurt[ing others]." And, in the terms of psychoanalysis, "the turning [out]ward of the destructive tendencies or thanatos."